Archive:Quality of life indicators - education

- Data from October 2013. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database.

This article is part of the Eurostat online publication Quality of life indicators, providing recent statistics on the quality of life in the European Union (EU). The publication presents a detailed analysis of many different dimensions of quality of life, complementing the indicator traditionally used as the measure of economic and social development, gross domestic product (GDP).

The present article focuses on the fourth dimension of the '8+1' quality of life indicators framework, education. Education is the formal process by which society, through schools, colleges, universities and other institutions, deliberately transmits its cultural heritage and its accumulated knowledge, values and skills to the next generation. Education, as the basis of human civilisation and a major driver of economic growth, benefits society, and it also has a major impact on the quality of life of individuals. A lack of skills and competencies limits the access to good jobs and economic prosperity, increases the risk of social exclusion and poverty, and may hinder a full participation in civic and political affairs.

Education is a complex and statistically challenging area: “soft” skills acquired in social life or knowledge obtained outside the formal educational system are often hard to measure, and comparability of formal qualifications (such as university degrees) over time, across countries and even within one country, can be problematic. This is one reason why information on formal education attainment and training has to be complemented by self-reported skills and participation in non-formal educational activities such as adult education and lifelong learning.

Source: Eurostat, EU-LFS (edat_lfs_9903)

Source: Eurostat, EU-LFS (edat_lfse_07))

Source: Eurostat, EU-LFS (edat_lfse_14) and (t2020_40)

Source: Eurostat, EU- LFS (edat_lfse_18)

Source: Eurostat, EU-LFS (trng_lfs_02)

Source: Eurostat (isoc_sk_cskl_i)

Source: Eurostat (isoc_ci_ifp_iu)

Source: Eurostat (edat_aes_l52)

Main statistical findings

Education in the context of quality of life

Broadly speaking, education refers to any act or experience that has a formative effect on an individual's mind, character, or physical ability. In its formal sense, education is the formal process by which society, through schools, colleges, universities and other institutions, deliberately transmits its cultural heritage and its accumulated knowledge, values and skills to the next generation. In our knowledge-based economies, education underpins economic growth, as it is the main driver of technological innovation and high productivity. Moreover, as a means to transmit knowledge through generations, education is the basis of human civilisation.

Besides its societal benefits, education is also a basic determinant of the quality of life of individuals. People with limited skills and competencies are excluded from good jobs and have fewer prospects for economic prosperity. According to research, early school leavers face a higher risk of social exclusion and poverty and are also less likely to participate in the civic life and political affairs of their society [1]. This is also because education enhances people’s understanding of the world they live in, and hence the perception of their ability to influence it.

Education is a complex field, sometimes difficult to measure. One of the difficulties in statistically assessing educational outcomes is the complexity of measuring “soft” skills, acquired in the social life of individuals, as well as the knowledge attained outside the formal educational system (e.g., through leisure reading, cultural activities, etc.). Moreover, the quality of formal qualifications (e.g. university degrees) is not always of the same level, both inside a country and across time, and between different countries. This is one of the reasons why there is a need to use complementary indicators to educational attainment, such as those related to self-reported and assessed skills, and also participation in life-long learning education and training.

In other words, to measure the overall level of education one needs both data on formal education attainment and training, as well as data related to other non-formal educational activities such as adult education and lifelong learning. This is an increasingly important aspect of the educational process and its assessment here covers the proportion of the population in further education and training, after having achieved a degree through the formal education system (for example, high schools and universities). It is worth mentioning that lifelong learning statistics include knowledge acquired through educational institutions and other informal, but still guided, training, but not random learning activities, like visits to libraries, and museums, or personal reading. These may also be complemented by data on assessed skills (such as those made available from PIACC) and self-reported ones (including the command of foreign languages and the use of computers).

Level of educational attainment

Data on educational attainment show that there are widespread differences between EU-28 countries (for example, between Scandinavia and the Balkan peninsula), as well as large discrepancies within countries (for example in Spain, where a large percentage of the population holds tertiary education degrees and another high percentage are early school leavers). These discrepancies reinforce the risk of developing inequalities within the EU-28 and social stratification within Member States.

Higher levels of educational attainment are generally linked to better occupational prospects and higher income for individuals, hence having a positive effect on their quality of life. People who have completed tertiary education improve their possibilities to secure a job: the unemployment rate decreases with the educational level. In Europe in 2011, low educated people were three times more likely to be unemployed than high-educated people. Especially in Slovakia, Lithuania and Latvia the gap in unemployment rates between low educated people and those with a tertiary degree exceeds 20 percentage points.

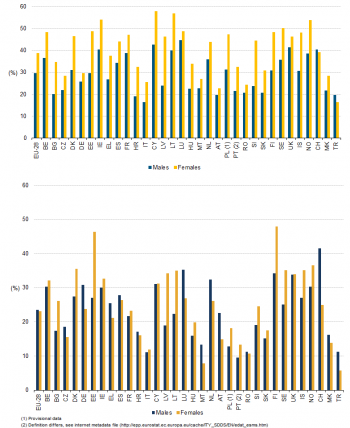

Tertiary education (ISCED levels 5-6) is the highest level of education that can be attained. It is provided by universities or other higher education institutions and includes programs with academic or occupational orientation, which may also lead to an advanced research qualification (Ph.D. or doctorate). In the EU-27 in 2011, just over one fifth (23.7 %) of the population aged 15 to 64 had achieved a tertiary education degree (see Figure 1). The percentages range from 33.7 % in Cyprus to 13.0 % in Romania. High percentages of working-age citizens who have attained the highest education levels are also recorded in Ireland and in the UK (both 33.3 %).

In five EU countries, a significant part of the working age population (more than one in three persons) has completed at maximum lower secondary education (ISCED level 2; Level 0 referring to pre-primary education, level 1 to primary and level 2 to lower secondary education). These three levels are part of compulsory schooling in most countries. More than six in ten working age Portuguese have only completed their compulsory education at best (educational attainment level 2 or lower). In Malta also 57.2 % of the working age population has only completed junior high school. Spain presents an interesting case, since 47.2 % of its working age population has only completed lower secondary education, while at the same time, 29.0 % of 15-64 year-old Spaniards, well above the EU-28 average, have completed either tertiary or postgraduate studies. When interpreting average education levels for such extended age groups however, it must be kept in mind that these include older generations raised in times where formal education systems were possibly quite different (e.g. shorter compulsory education periods), while the potential impact of large-scale immigration should also be taken into account.

Overall in the EU-27, almost half of the working age population (46.6 %) has completed at most upper secondary education (Figure 1). The EU countries with the highest percentages of university graduates are Cyprus, Ireland, the United Kingdom and Finland, where about 1/3 of the population has completed tertiary or postgraduate studies. The lowest prevalence of working age university graduates is recorded in Romania (13.0 %), Italy (13.1 %) and Malta (14.3 %). However, even in countries with low overall numbers of university graduates, younger generations are more likely to have completed tertiary education. The differences in the proportion of the population having a tertiary educational attainment between the 25-34 and the 45-54 age groups are sharpest in Italy, Latvia, Cyprus, Romania, Portugal, Malta, Croatia, Ireland and Poland. In other countries, most notably Estonia, Germany, and Finland, the improvement has been smaller. Indeed, Finish and German males aged between 45 and 54 were more likely to have completed tertiary education in 2011 than their 25-34 year-old compatriots. But these are just exceptions to the clear trend throughout the EU that younger Europeans are better educated than older age groups.

Across the EU-28, more than one in five men (22.5 %), and almost one in four women (24.9 %), aged between 15 and 64, have graduated from tertiary education, according to the latest available (end 2011). Women with tertiary education attainment are more numerous than men in almost all countries surveyed. Some countries are exceptions to this general trend (Switzerland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, Malta as well as Turkey), where the proportion of men was higher than for women in ISCED levels 5-6. It is worth noting that women’s “dominance” in tertiary education is a recent phenomenon. For example, as shown in Figures 2 and 3, while the proportion of university graduates is almost identical among men and women aged between 45 and 54 in the EU, the picture is completely different in the 25-34 age group, where women clearly outnumber male university graduates. More than half of women aged between 25 and 34 in Cyprus, Ireland, Latvia, and Sweden, have completed tertiary or postgraduate education.

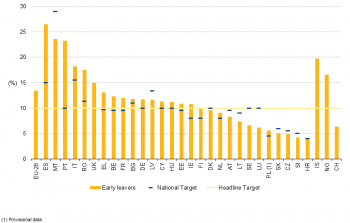

At the same time, the Member States have committed themselves to reduce the school drop-out rates below 10.0 % by 2020. The term “early school leaver” generally refers to a person aged 18 to 24 who has finished no more than a lower secondary education and is not involved in further education or training; their number can be expressed as a percentage of the total population aged 18 to 24. In setting the 2020 headline target, the EU has identified early school leaving (ESL) as an obstacle to economic growth and employment, since it hampers productivity and competitiveness, and fuels poverty and social exclusion [2]. The challenge of limiting ESL is especially daunting for Spain, where 26.5 % of its 18-24 year olds in 2011 were early leavers (see Figure 3). Similarly, 23.2 % of young Portuguese in this age group were early leavers in 2011. Conversely, other EU countries, like Croatia, Slovakia, Sweden, Poland, and Luxembourg, are on course to achieve their national target for limiting ESL and have already overshot the EU’s headline target.

NEET: young people neither in employment nor in education and training

Perhaps the most worrying trend for young Europeans in the age group 18-24 is that some of them are neither in employment nor in education or training. Long periods of absence from the labour market, and failure to acquire knowledge and occupational skills have been shown to undermine the future prospects of young Europeans. The so-called “NEET” indicator shows the share of young persons aged 18 to 24 who are not employed and not involved in further education or training. In 2011, 16.7 % of Europeans aged between 18 and 24 were in this category. The problem appears to be especially acute in Bulgaria (26.3 %), Italy (25.2 %), Greece (24.4 %), Ireland (24.0 %) and Spain (23.1 %), where between one in five and one in four 18-24 year-olds were NEET in 2011 (Map 1).

On the other hand, Nordic countries, as well as Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Denmark, Austria, Germany, Malta, the Czech Republic and Slovenia have managed to limit this phenomenon and keep most of their youngsters either in the job market, or in training and educational programs. The latter group of countries, with the exception of Finland and Sweden, record also the lowest youth unemployment rates.

Lifelong learning

In any case, the idea that education finishes with the end of school or university seems parochial nowadays. Employability largely depends on the skills that each job-seeker acquires throughout his or her professional life. In this sense, lifelong learning has become a necessity in the highly competitive environment of the European job market, as the needs of companies continuously evolve, together with the technologies used by them.

The term “lifelong learning” encompasses all learning activities undertaken throughout life for personal or professional reasons, after the age at which usually most people have finished their schooling. The target population of Eurostat's lifelong learning statistics is all members of private households aged between 25 and 64, and the indicator measures the percentage reporting they received education or training in the four weeks preceding the survey. Data are collected through the EU Labour Force Survey (LFS). Through the continuous participation in learning activities a person can improve knowledge, skills and competences useful for his or her career. It is worth clarifying that lifelong learning statistics cover formal and non-formal guided education and training, and exclude self-learning activities. For example, evening or language courses at universities, or other institutions, and computer skills courses are measured as lifelong learning. On the other hand, reading a history book, or visiting a science museum, although conceptually belong to the concept of lifelong learning, are not statistically measured within this indicator.

Data from 2011 shows that Denmark, Sweden and Finland are pioneers in lifelong learning participation rates. Almost one in three Danes and almost one in four Swedes and Finns participate in such programs. The EU average is much lower, as only 8.9 % of those between 25 and 64 take part in structured lifelong learning courses. This average is quite low compared with other European countries outside the EU (Norway, Iceland, Switzerland).

It appears that people in the EU who already hold higher education degrees tend to continue their training through lifelong learning. In the EU-27, 16.0 % of the population aged 25 to 64 holding tertiary education degrees participated in lifelong learning programs, compared with 7.6 % of secondary education graduates, and 3.9 % of those who have only completed primary education (Figure 4). The differences between countries however are so stark that there are countries (such as Greece or Hungary) where a lower percentage of people with a high level of education receive lifelong learning courses, than people with a low level of education in some other countries (such as the Nordic ones).

Computer and language skills

The ability to use a computer and the command of a foreign language are among the most important competencies, not only for the job market but also to take advantage of education, information and cultural opportunities in our increasingly digital and globalised societies. While about one third of Europeans aged 25 to 54 have a high computer literacy level (the level of computer skills being formally measured through the ability to perform standard operations on a computer [3]), there is a digital literacy divide: about one out of every four Europeans cannot perform even elementary operations on a computer (Figure 5). This percentage is very low (less than 10.0 %) in Nordic countries, but exceeds 35.0 % for Italy, Lithuania and Poland, and reaches 40.0 % for Poland, Cyprus and Greece, while it is extremely high for Bulgaria (49.0 %) and Romania (59.0 %).

It is also worth noting that almost half of the population in this age group in Romania, and around one out of three persons in Cyprus, Bulgaria and Greece, report that they have never used the internet (Figure 6). On the other hand, usage of the Internet is almost universal in this age group in Denmark, Finland and the Netherlands, indicating a «digital divide» between Northern Europe, and South and Eastern Europe. Differences in educational attainment levels (especially concerning tertiary education) may explain part of this digital literacy gap, which deserves further investigation.

In a European Union of 28 Member States speaking 24 different languages, the efficient command of foreign languages is becoming increasingly important, not only as a means of communication, but also to facilitate workers’ and students’ mobility. In nearly all countries (and also for EU-28 as a whole), more than half of the population report that they command at either a good or proficient level the foreign language reported as the best known in their country (Figure 7; N.B.: English for most of the EU countries, except for the Baltic states for which it is Russian, Luxembourg for which it is German, and Slovakia for which it is Czech). Italy is the only exception, where only a third of Italians report a good or proficient command of the most common foreign language in their country (English), while Poland, France, Germany and Romania are also characterised by low rates.

In nearly all European countries though, the above rates improve significantly by several percentage points (in some cases exceeding 10 percentage points) for younger Europeans, indicating a clear trend (this holds for countries where English is the most commonly used foreign language; in contrast, in the Baltic countries, rates are expectedly declining, as younger people tend not to learn Russian, which is the most commonly known foreign language in these countries).

Conclusions

In the EU-27 in 2011, over one fifth (23.7 %) of the working age population had achieved a tertiary education degree, while almost half of them (46.6 %) had completed at most upper secondary education. However, there is a clear trend throughout the EU that younger Europeans are better educated than older age groups. The gender gap in higher education has not only disappeared, but has also been reversed: the proportion of women with tertiary education attainment is higher than for men in almost all countries. While the proportion of university graduates is almost identical among men and women aged between 45 and 54, in the 25-34 age group women clearly outnumber male university graduates.

Reducing school drop-out rates or “early school leavers” remains a challenging target for the EU, and for some countries even more so. Similarly, there are concerns for the so-called “NEET”, i.e. young persons aged 18 to 24 who are neither employed, nor involved in further education or training. In 2011, 16.7 % of young Europeans aged between 18 and 24 were in this category.

Overall in the EU-27, active participation of adults in life-long learning activities is rather low: only 8.9 % of the population between 25 and 64 take part in structured lifelong learning courses. It appears that people who already hold higher education degrees tend to pursue lifelong learning at considerably higher rates than people with lower educational attainment levels.

About one in three Europeans, in most European countries, has a high level of basic computer skills. In general, higher income earners and younger generations are more likely to be able to use a computer than their counterparts. There is however a «digital divide» as regards computer literacy, between Northern Europe on the one hand, and South and Eastern Europe on the other. At the same time, between one third and over two thirds of Europeans report that they have at least a good level of knowledge of the foreign language reported as the best known in the country.

Data sources and availability

As a dimension of the Quality of Life framework, education refers to acquired competences and skills; to the continued participation in lifelong learning activities; and to aspects related to the access to education.

- Competences and skills are measured through data on educational attainment of the population (provided by the Labour Force Survey - LFS), as well as an early school leavers indicator provided in education and training statistics. These are to be complemented by measures on self-reported (foreign language and computer knowledge) and assessed skills (currently available through the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC)).

- Life-long learning covers the proportion of the population in further education and training (provided by LFS)

- Additional indicators related to opportunities for education are to be developed.

Context

Education affects the quality of life of individuals in many ways. People with limited skills and competencies tend to have worse job opportunities and worse economic prospects, while early school leavers face higher risks of social exclusion and are less likely to participate in civic life. But beyond pragmatic considerations, education is a value of our societies in itself, since it allows people to better understand the world they live in.

Education has a very important place in European policy. Two headline targets of the overarching Europe 2020 Strategy come from this field: at least 40 % of its 30-34–year-olds should be university graduates, and drop-outs from education and training should be less than 10% by 2020. Also, making lifelong learning and mobility a reality, as well as improving the quality and efficiency of education and training are objectives set in the strategic framework for European cooperation in education and training (ET 2020, Council conclusions of 12 May 2009). Another important European strategy promotes multilingualism with a view to strengthening social cohesion, intercultural dialogue and European construction (Council Resolution of 21 Nov. 2008).

See also

- Quality of life indicators (online publication)

Further Eurostat information

Main tables

- Europe 2020 indicators, see:

- Headline indicators (eu2020_h)

- Education (eu2020_ed)

- Computers and the Internet in households and enterprises (t_isoc_ci)

- E-Skills of individuals and ICT competence in enterprises (t_isoc_sk)

- Lifelong learning (t_trng)

- Educational attainment and outcomes of education (t_edat)

Database

- Computers and the Internet in households and enterprises (isoc_ci)

- E-Skills of individuals and ICT competence in enterprises (isoc_sk)

- Lifelong learning (trng)

- Educational attainment and outcomes of education (edat)

- Educational attainment level: detailed results (edata)

- Transition from education to work, early leavers from education and training (edatt)

- Language skills (edat_aes_l)

Dedicated section

- Quality of life indicators, see Education

Source data for tables, figures and maps (MS Excel)

Notes

- ↑ Europe 2020 Target: Early Leavers from Education and Training, European Commission

- ↑ Europe 2020 Target: Early Leavers from Education and Training, European Commission

- ↑ Low, medium and high levels of basic computer skills denote Individuals who have carried out 1 or 2 of the 6 computer-related items, Individuals who have carried out 3 or 4 of the 6 computer-related items, Individuals who have carried out 5 or 6 of the 6 computer-related items respectively. Six computer-related items were used to group the respondents into levels of computer skills: copy or move a file or folder; use copy and paste tools to duplicate or move information within a document; use basis arithmetic formula (add, subtract, multiply, divide) in a spreadsheet; compress files; connect and install new devices, e.g. a printer or a modem; write a computer program using a specialized programming language.